Some programs already in place, many more needed

Cleveland Clinic president and CEO

Too many of the stories we hear about opioid-related deaths start the same way – with a patient prescribed a pain medication for an injury or medical procedure.

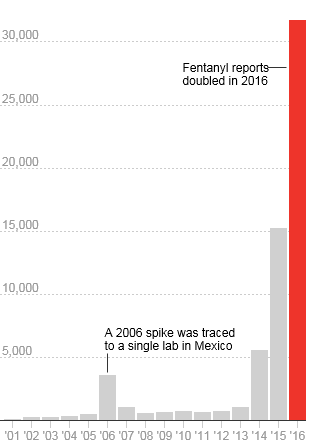

The stories then progress to street drugs like heroin or fentanyl, leading all too often to death. In 2016, about 60,000 Americans died of opioid abuse, an American death toll greater than the whole of the Vietnam War.

This has to stop and healthcare providers have a key role in turning the tide. One of the most sobering statistics, from a physician’s point of view, is that over 75 percent of opioid and heroin deaths begin with a prescription pain killer. The healthcare industry bears some responsibility.

That’s not to say that patients aren’t in legitimate pain. They are, maybe as many as 100 million by some estimates. But we as healthcare providers have to approach pain differently, smarter.

Declaring the opioid crisis a National Public Health Emergency is a good first step. But we in healthcare can’t wait for Washington. We have approaches at our disposal that can effect very real change.

Better policies have shown to make a difference quickly. In just the past few months, we’ve:

- Reduced the number of opioid prescriptions exceeding 3 days by 50 percent in our emergency departments, simply through education and communication.

- Reduced the number of patients receiving opioids by one-third in a group of colorectal surgery patients.

- Hired a full-time Doctor of Pharmacy, who as a pain-management specialist can improve prescribing practices and clinical care.

- Designated every hospital unit with “pain champions,” who are conversant with alternative pain strategies.

What it boils down to is this: healthcare providers have to make this a priority and we have to give physicians the tools they need to effect change.

Essentially, we can attack the opioid epidemic in four ways: giving healthcare providers the prescribing tools and resources they need; insisting on team engagement among hospital departments; tracking prescribing data and demanding accountability; and sharing information with other hospitals in the region.

Our electronic medical records system has been an indispensable tool. It has allowed us to connect directly to the Ohio Automated Rx Reporting System (OARRS); now, a physician can see a patient’s history of controlled substances within seconds while formulating a treatment plan. Also, our patient-provider agreements and consents are stored electronically so anyone who cares for that patient can see it, review it and update it as appropriate.

At the same time, we can use the electronic medical record to gather data so that we truly understand current practice – What type of patients are being prescribed narcotics? Which departments prescribe opioids most often? – then use that data to standardize care across the system.

Here are a few more approaches we’re using at Cleveland Clinic:

A Twist on “Just Say No”: Saying “no” to patients who are seeking narcotics for pain relief is difficult. That’s why we’ve instituted training courses for physicians on how to decline opioid requests from patients, with an emphasis on being compassionate. These are difficult conversations and the stakes are high. We must help our physicians navigate this by giving them the skills, strategy and practice to show empathy while managing emotion, setting boundaries and employing de-escalation tactics when needed.

Getting Back on TREK: Back pain strikes about 31 million Americans at some point during their lives. All too often, the first-line treatment is surgery or pain killers. At Cleveland Clinic, we are offering a different approach. Back on TREK (Transform Restore Empower Knowledge) is a pilot program treating patients with chronic low back pain (with or without leg pain), with the goal of restoring function through non-surgical treatment approaches and providing patients with tools to manage their pain without narcotics. The program utilizes a combined treatment approach of psychologically informed physical therapy; pain neuroscience education and behavioral medicine sessions utilizing cognitive behavioral therapy and psychological education techniques. More than 60 percent of patients showed significant improvement in pain and disability; over half demonstrated significant reduction in fatigue, pain interference, and overall physical health.

Painless mastectomy: An experimental drug, Exparel, is a local, time-released anesthetic used after a mastectomy to help patients with the worst of the pain — the first four days — so patients can avoid opioids.

Narcotic-free colorectal surgery: A program at Cleveland Clinic Akron General replaces narcotics with pre-surgical pain management, peripheral nerve blocks during procedure, and encouragement for the patient to get out of bed and move around within 4 to 6 hours of getting to the recovery floor. Of 80 patients in the program, one-third avoided narcotics. As a result, readmission rates and surgical costs dropped, hospital stays were shortened by 50 percent, risk of complications were reduced, and recovery improved with less pain.

New “ERAS” of recovery: Several medical centers, including Cleveland Clinic, have been developing the concept of “fast-track” or “enhanced” recovery after surgery. Recently, comprehensive research has indicated that an ERAS (“Enhanced Recovery After Surgery”) methodology that permits patients to eat before surgery, limits opioids by prescribing alternate medications, and encourages regular walking reduces complication rates and accelerates recovery after surgery. ERAS can reduce blood clots, nausea, infection, muscle atrophy, hospital stay and more. Patients are also given a post-operative nutrition plan to accelerate recovery, and physicians are using multi-modal analgesia, limiting the use of narcotics.

The good news is that the fight against the opioid epidemic is moving in the right direction. Everyone – hospitals, physicians, lawmakers, law enforcement and the general public – see this as the national emergency that it is.

By leveraging the tools at our disposal – or by creating new tools – we can save lives.

Link to original article here: Healthcare Providers Helped Bring About the Opioid Epidemic; Now It’s Time to Help End It

You must be logged in to post a comment.